Climate Change: Winners and Losers

Lesson 4: Desert Belts

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3: Desertification Review

Desertification:

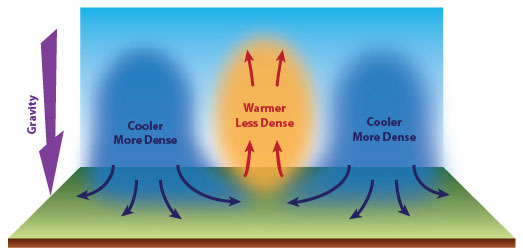

We have just seen evidence of two important properties about the air in our atmosphere:

1) Warmer air rises, cooler air sinks; and

2) Warmer air can hold more moisture than cooler air.

So what does this have to do with Earth's desert belts? It turns out, just about everything.

In general, the EM radiation from the Sun strikes the Earth most directly at the Equator. This makes the Equatorial region the overall warmest on Earth. The warm air over the Equator rises up into the atmosphere. It also carries a lot of moisture into the atmosphere.

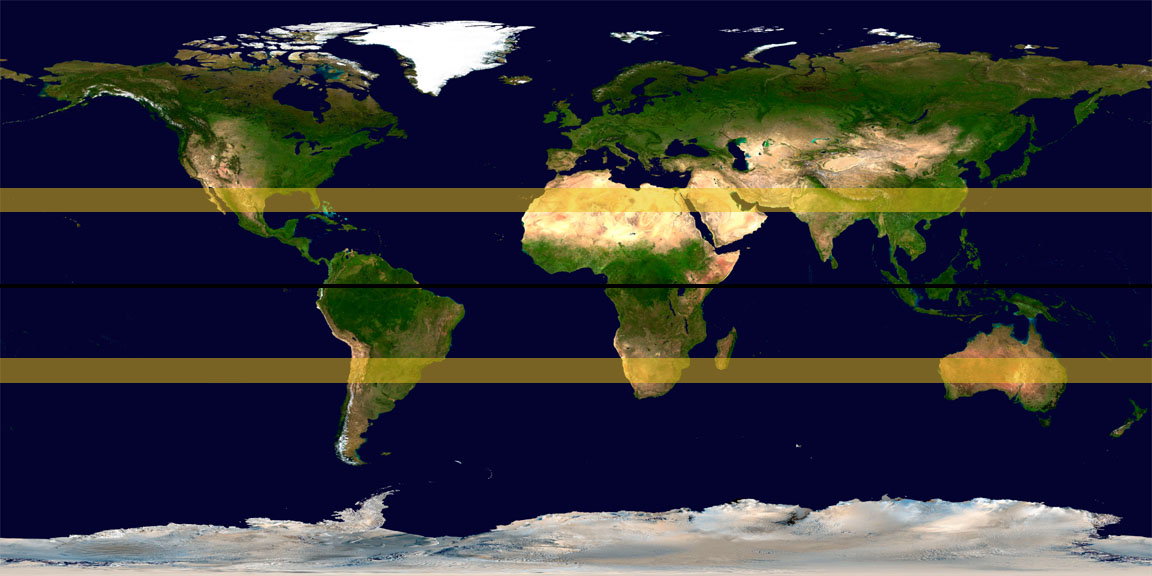

This warm air begins to cool as it rises. As it cools, it loses its ability to hold moisture. The moisture condenses back into water droplets and falls back to Earth as rain. This is why it tends to rain so much in the tropics. The black line on the map below represents the Equator. Notice how green the Earth is around this line? Most of the Equatorial region of the planet is rain forest.

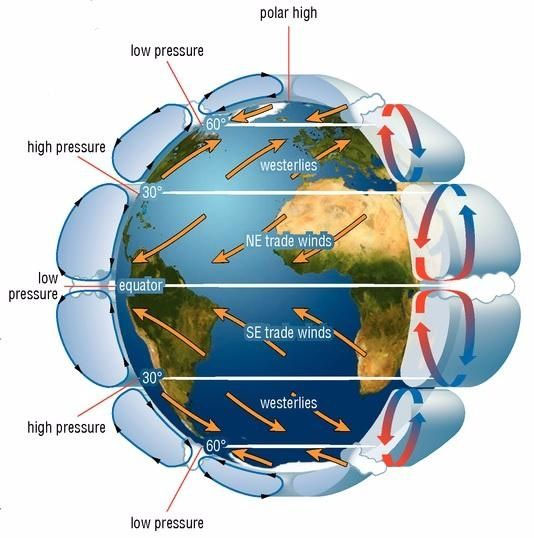

By the time this Equatorial air gets higher into the cooler parts of the atmosphere, it has lost most of its moisture. It is now much drier. This very dry air then starts moving northward in the Northern Hemisphere and southward in the Southern Hemisphere. As it moves away from the Equator, it cools off even more and becomes denser. Eventually the cool, dry air falls back to Earth. This creates a general pattern of air movement that affects our weather and impacts the amount of rain that falls over different parts of the planet. The diagram below shows the general circulation of air over Earth:

There is a lot going on in this diagram. The orange arrows show air movement near the planet's surface. But notice the two pairs of red and blue arrows on the right, near the Equator. They show air movement in the atmosphere. I hope you will notice that at about 30º north and south of the Equator, this cold, very dry air falls back to Earth. Since there is little or no moisture in the air, there will be very little rain. This is why many of the Earth's deserts can be found in a "belt" that encircles the Earth along these two regions, both approximately 30º north or south of the Equator. The yellow bands on the map below represent these regions.

There are deserts outside of this region. They have different causes. But the ones in the desert belts are the ones we need to be most concerned about, because as Earth's atmosphere warms up, the size and position of the desert belts will change. They will begin to widen and move into higher latitudes--further south in the Southern Hemisphere, and further north in the Northern Hemisphere.

In the Southern Hemisphere, much of the expansion will take place over water. But look at the Northern Hemisphere. If the increase and northward movement of the northern desert belt is great enough, much of the United States and southern Europe could become desert. In the US, water sources in the Midwest would become endangered. Much of our farmland could be lost to desertification--the changing of arable land, or land suitable for growing crops, into desert. Europe could face similar problems.

Parts of the United States have experienced desertification in the past. In the 1930s, a combination of changing weather patterns and poor land stewardship turned large areas of Kansas and Oklahoma farmland into semi-desert. Crops failed. Most of the region's top soil was lost--picked up by strong winds and blown away--because there were few plants in the ground holding it in place. This region of the country became known as the "Dust Bowl." Giant sandstorms engulfed entire towns in dark clouds of sand and dust.

One of my favorite stories about the Oklahoma dust bowl is Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse. I recommend it.

But as much as I enjoyed reading it, I would hate to see farmers in the Midwest today face a similar situation.

We have looked at only two of the major challenges posed by climate change that we are likely to face over the next few decades. There will be additional problems, such as the increasing acidity of the oceans, and increasingly frequent and profound weather extremes like storms and droughts. But not every change will affect everyone, and some of these challenges can be less destructive to us if we plan for them. For example, changing where and how we build new homes can help to reduce the impact of destructive storms or flooding.

As I wrote in our first lesson, climate change is neither good nor bad. But it is happening, and like most changes in the natural world, some things will benefit, and some will suffer. In our final lesson, we will try to look into the future and predict who, or what, the likely "winners" and "losers" will be. There may be some surprises.

Go to Review